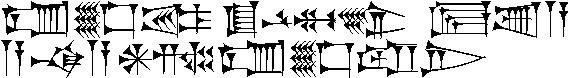

The Sumerian proverbs were written in cuneiform on clay tablets in both the Sumerian and Akkadian languages. The proverbs may have been used as textbooks in the Sumerian educational system to teach students to write Sumerian (which by 1700 BCE was no longer a spoken language). So, there is a bit of playfulness in the maxims.

OBSERVATIONS ABOUT ANIMALS

Some of the proverbs seem to be literal descriptions of animal (and human) behavior in the natural world (no mythological creatures are mentioned).1

Wild Animals

The proverbs indicate several human attitudes toward wild animals in the Bronze Age: (1) wild animals compete with humans for food; (2) they are dangerous.

1.9 If food is left over, the mongoose consumes it; if it leaves any of my food, the stranger consumes it.

1.20 What the weather might consume, the beasts spared; what the beasts might consume, the weather spared [i.e., the beasts ignore the perishable food and consume the food that humans have stored for the future].

2.94 Upon escaping from the wild ox, the wild cow confronted me!

2.113 He who pets the neck of a treacherous dog is petting the mane of a wild dog.

Domestic Animals

Already by the Bronze Age, humans had begun to assign domestic animals certain personality traits and functions.

The ass was slow and obstinate.

2.75 My ass was not made fit to run quickly; he was made fit to bray!

2.76 The ass lowered its face and the owner of the ass patted its nose, saying “We must get up and away from here! Quickly! Come!”

2.77 The ass eats its own bedding.

The ram was a dangerous animal to be respected, but lambs were food.

1.111 Inside: a ewe; outside: a ewe! The mate is most fecund. Even if he destroys a shepherd, you should not destroy him!

1.112 Did you lift your horns against me? Who is it that you are butting?

1.55 When he had a lamb, he had not meat; when he had meat, he had no lamb.

The ox was a useful but occasionally lazy or stupid animal.

2.91 The ox is ploughing; the dog is spoiling the deep furrows.

2.84 The ox: its life is prolonged; it’s always lying down.

2.93 A stranger’s ox eats grass, but my ox lies down in the meadow!

2.87 The ox is too close to the threshing floor; the seed grain will not be sown.

2.90 The ox, having made dust, in its own eyes it was flour.

Dogs were sometimes hungry and mischievous but also usefully employed in hunting or guarding.

2.109 A begging dog goes from house to house.

2.110 It is the dog that eats things defiling! It is the dog that does not leave any food for the next morning.

2.112 The smith’s dog could not overturn the anvil; it overturned the water pot instead [possibly a metaphor meaning that an aggressive person who is frustrated in his attack takes it out on a weaker person].

2.107 Dogs at their . . . wait for instruction: “Where has it gone?” “Bring it back!” “Stay where you are!”

2.116 A dog springs up, a lance is propelled; each does its damage.

1.65 In a city of no dogs, the fox is overseer.

There are very few proverbs that mention pigs and no mention of chickens or cats.

ANIMALS AS METAPHORS FOR HUMAN BEHAVIOR

In the Sumerian proverbs, we see the beginning of the use of animals for lessons in human behavior (later picked up in Aesop’s fables).

The Fox

The fox (as depicted in the proverbs) is a small creature that has an exaggerated sense of self-importance and an underlying inferiority complex. He bullies his friends, swaggers around with a stick, and tries to hurt the ox. The fox has big plans to conquer a few cities but is scared away by the dogs and slaves.

2.62 The fox could not build his own house, so he came to the house of his friend as a conqueror.

2.65 A fox trod upon the hoof of a wild ox; “It didn’t hurt” (said the wild ox).

2.66 The fox had a stick with him: “Whom shall I hit?” He carried a legal document with him: “What can I challenge?”

2.67 The fox, having urinated into the sea, said “The whole sea is my urine.”

2.69 The fox said to his wife: “Come! Let us crush the city of Uruk with our teeth as if it were a leek; let us strap the city of Kullab upon our feet as if it were a sandal! When they had not even come within a distance of 600 GAR [2.25 miles] from the city, the city dogs began to howl. All the slave girls of Tummal with the cry “Go home! Get along!” howled menacingly about the city.

2.70 How clever is the fox! He has outwitted the . . . bird!

Other Animals

Here are a few examples where human behavior is compared to that of an animal.

1.68 Into a plague-stricken city, one must drive him by force like a pack-ass.

2.81 I will not marry a wife who is only three years old like an ass does [a protest against child marriage].

2.85 Like an ox that has escaped from the threshing floor, he is filled with rebelliousness.

Stereotyping of animals has been going on for nearly four thousand years. While some of the observations are accurate, many of the proverbs impute human attitudes or behaviors to the animals or contain an element of implicit judgement about an animal’s behavior. The ideas of these early proverbs have persisted in literature and color our views of certain animals today, especially since most people have no firsthand contact with animals other than pets and garden predators.

I have not included all of the proverbs related to animals. The numbers and translations are based on Edmund I. Gordon, Sumerian Proverbs: Glimpses of Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, 1959).